8: Gossip Tour

Did you hear what they’re saying about Jackson? Do you think that story about Lee is true? I’d like to give you the skinny on both of them.

It’s no secret that Jackson was an alcoholic, and he started drinking at an early age. But he wasn’t drinking in order to stimulate his creativity. In fact it was the opposite. Unfortunately he drank instead of working, and that drove Lee crazy. It’s the main reason she wanted to move to the country, to get him away from his drinking buddies. And it worked. Out here he found a local doctor who kept him on the wagon for two years, from 1948 through 1950, and those were his most productive years.

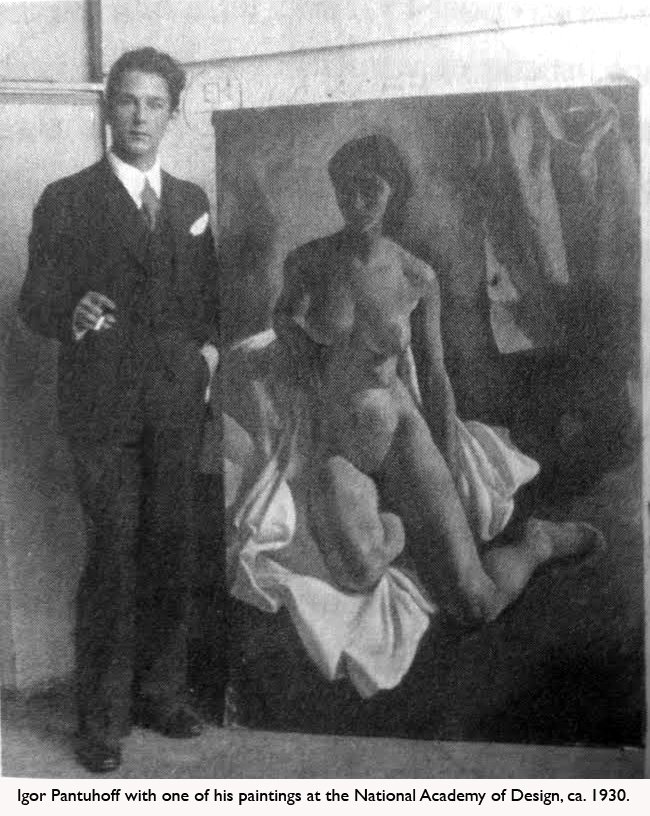

Before Lee met Jackson, she had a nine-year relationship with a handsome White Russian émigré named Igor Pantuhoff.  They met in art school, and lived together in the 1930s. She was Jewish, and Igor’s family was anti-Semitic, but somehow they got over that, and although they weren’t married they acted like they were. In spite of being very poor, they were a glamorous couple, in high bohemian style. Lee had a lovely figure, and modeled for fashion illustrators before she got a job on the WPA Federal Art Project, an employment program that paid artists a weekly wage during the Great Depression.

They met in art school, and lived together in the 1930s. She was Jewish, and Igor’s family was anti-Semitic, but somehow they got over that, and although they weren’t married they acted like they were. In spite of being very poor, they were a glamorous couple, in high bohemian style. Lee had a lovely figure, and modeled for fashion illustrators before she got a job on the WPA Federal Art Project, an employment program that paid artists a weekly wage during the Great Depression.

Jackson worked on that project, too, but he had trouble meeting the deadlines. In addition to his drinking problem he suffered from mood swings. He tried psychiatric treatment, but he was never properly diagnosed. You may have heard that he was bi-polar, or that he was oxygen-deprived at birth, but no one really knows the reason for his emotional problems. They caused a lot of trouble in his social life, especially his romantic relationships. In 1933 he dated Lillian Meyer, a fellow student at the Henry Street Settlement, where they were taking free art classes, and in 1937 he had an intense crush on a folk singer, Becky Tarwater. Both young women were frightened off by his drinking and unpredictable temper.

You have to give Lee credit for taking him on. Their first meeting, at a dance in 1936, wasn’t exactly love at first sight. She was a great dancer, and was having a wonderful time when this drunken stranger cut in on her, stepped all over her feet, and propositioned her! She just brushed him off. People often assume that Jackson was a womanizer, but in truth, he didn’t know how to charm or sweet-talk women, and he certainly didn’t sweep Lee of her feet that night. Five years later, they met again, and she recognized him. Fortunately it was during a visit to his studio, when she also saw his work, which did seduce her. She fell in love with both the art and the artist, and moved in with him in 1942.

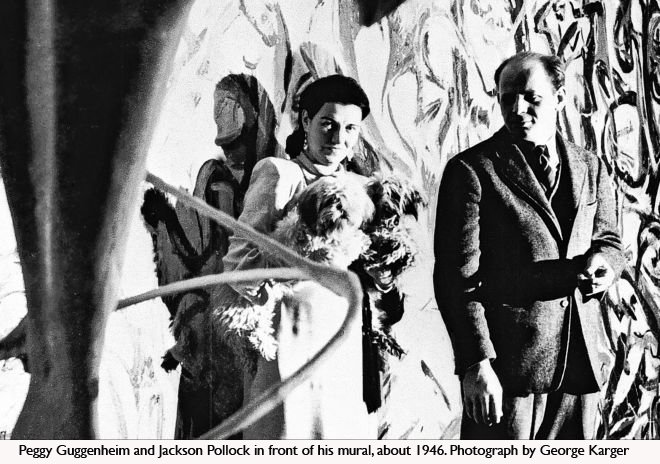

Lee often said she wasn’t interested in marriage, but after her father died in 1944 she had a change of heart. She was already in her late thirties, and I think she wanted some stability. So she gave Jackson an ultimatum: marriage, or split. He said OK, marriage, but it has to be in church. Where that came from I don’t know, except that some of Jackson’s friends insist that even though he seemed like the classic rule-breaking rebel, he actually had a strong conventional streak. But a church wedding? He was agnostic, and she was Jewish. After several inquiries, Lee found a Dutch Reformed minister at the Marble Collegiate Church who agreed to marry them, which he did on October 25th, 1945, just before they moved to Springs.  Peggy Guggenheim, Jackson’s dealer and patron, was supposed to be a witness, but she cancelled at the last minute. Her excuse was, “Aren’t you two already married enough? And besides, I have a lunch date.” So the church janitor was the witness instead of Peggy.

Peggy Guggenheim, Jackson’s dealer and patron, was supposed to be a witness, but she cancelled at the last minute. Her excuse was, “Aren’t you two already married enough? And besides, I have a lunch date.” So the church janitor was the witness instead of Peggy.

Jackson was lucky to have strong, capable women like Lee and Peggy to support him and manage his career. He was unknown when he and Lee met, and when Peggy took him on as a protégé in 1943. . It was Peggy who pushed his work to the few influential critics and curators who were interested in modern American art, and who got collectors to take a chance on it. Because of the abortive seduction scene in Ed Harris’s movie, “Pollock,” many people believe he and Peggy had an affair, but not according to Peggy. In her tell-all memoir, “Confessions of an Art Addict,” she owns up to many lovers, but says flatly that her relationship with Jackson was strictly business. She paid him a monthly allowance so he could paint without having to take outside jobs, and she lent him and Lee the down payment on this property.

When they moved out here, ten days after the wedding, they really

burned their bridges. They gave up the Greenwich Village apartment, and

moved here full time. They got a local bank mortgage for $38 a month, and were living on Peggy’s allowance, which, as Jackson complained, just about didn’t pay the bills. Fortunately they were befriended by Dan Miller, who owned the Spring General Store, and he gave them credit. They also had fresh vegetables from their garden, and the clams they dug out of Accabonac Harbor. And somehow they always had enough money to buy art supplies. A good thing, because they both became very productive, and Jackson had plenty of work for Peggy to sell and repay her loan.

When they moved out here, ten days after the wedding, they really

burned their bridges. They gave up the Greenwich Village apartment, and

moved here full time. They got a local bank mortgage for $38 a month, and were living on Peggy’s allowance, which, as Jackson complained, just about didn’t pay the bills. Fortunately they were befriended by Dan Miller, who owned the Spring General Store, and he gave them credit. They also had fresh vegetables from their garden, and the clams they dug out of Accabonac Harbor. And somehow they always had enough money to buy art supplies. A good thing, because they both became very productive, and Jackson had plenty of work for Peggy to sell and repay her loan.

Don’t believe the starving artist myth. Jackson eventually made serious money from his work. It took several years, but by the early 1950s, he was actually quite well off. In 1952, his most lucrative year, he made nearly $11,500. The median family income was $3,900, so he was in the top four percent! Not bad for a guy who never held a nine-to-five job. Unfortunately, by that time his drinking problem was getting worse, and he was trying all kinds of miracle cures and quack remedies to control it. The only thing he didn’t try was quitting.

By 1955 Lee was pretty desperate, and they both started going to a psychiatrist in the city. But no sooner would he leave the shrink’s office than he would head straight for the Cedar Bar. There are plenty of stories, most of them true, about his wild behavior when he got liquored up—some of it just for show, and some of it really out of control.

Into this scene, early in 1956, walks Ruth Kligman, a 26 year old aspiring artist with Liz Taylor looks, who set her cap for Jackson. She had asked another young painter friend, Audrey Flack, to list the most important artists of the day, and Audrey said, “Jackson Pollock, Willem de Kooning, and Franz Kline.” Ruth said, “In that order?” Audrey said “Yes,” so Ruth had affairs with them in that order. She threw herself at Jackson and of course he caught her, but Lee soon found out about it. She and Jackson had planned a trip to Europe, but Jackson begged off. He said it was because he had to keep seeing his psychiatrist, but the treatment he really wanted was what he was getting from Ruth.

Into this scene, early in 1956, walks Ruth Kligman, a 26 year old aspiring artist with Liz Taylor looks, who set her cap for Jackson. She had asked another young painter friend, Audrey Flack, to list the most important artists of the day, and Audrey said, “Jackson Pollock, Willem de Kooning, and Franz Kline.” Ruth said, “In that order?” Audrey said “Yes,” so Ruth had affairs with them in that order. She threw herself at Jackson and of course he caught her, but Lee soon found out about it. She and Jackson had planned a trip to Europe, but Jackson begged off. He said it was because he had to keep seeing his psychiatrist, but the treatment he really wanted was what he was getting from Ruth.

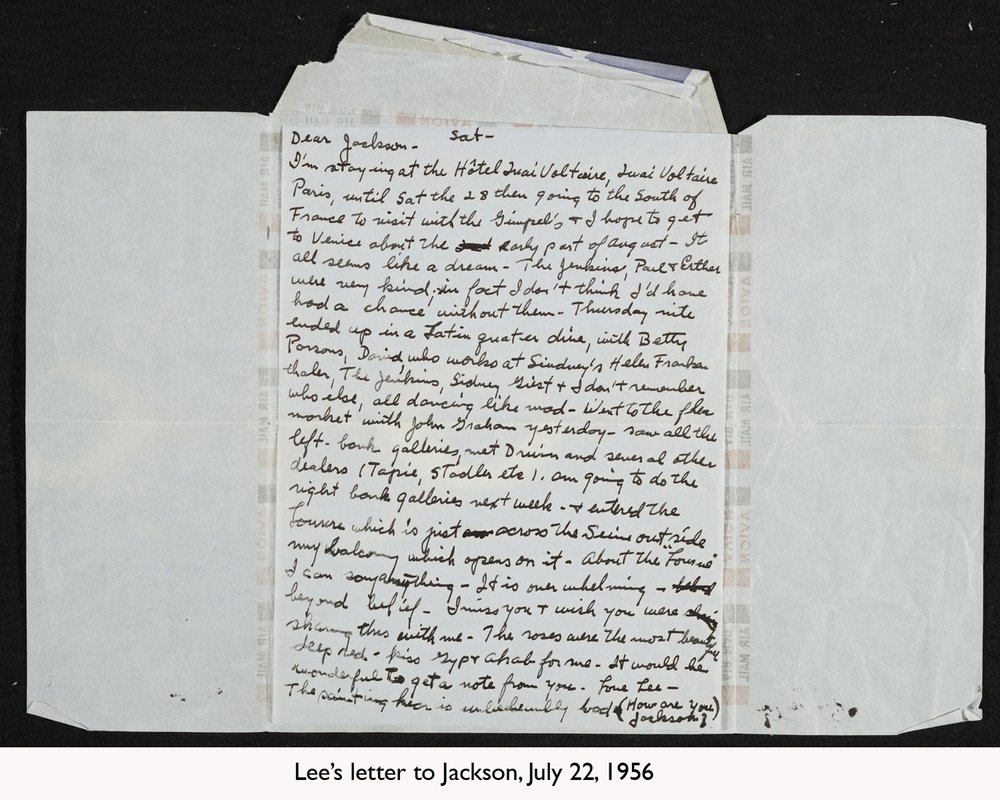

So in mid-July Lee went off to Europe alone, hoping the affair would burn itself out before she got back. No sooner had her ship sailed than Jackson moved Ruth into the house. But their love nest was no bed of roses. He was drinking heavily, and his dark moods frightened her. Plus his friends, who were loyal to Lee, stopped inviting them to parties, so she was often stuck alone in the house with him. Whether she was bored, or lonely, or scared, or maybe all three, she sometimes had second thoughts and went back to the city a couple of times.

In August she invited Edith Metzger, a friend from the city, to come out to the country for the weekend. Edith was the same age as Ruth, and would be much better company than Jackson. So on August 11th the two women took the train to East Hampton and Jackson picked them up in his Oldsmobile 88 convertible, a big, heavy car with lots of horsepower.

Jackson may have been infatuated with Ruth, but he didn’t want to give up on Lee, who after all was managing his career. She put her own career on hold to promote him, and he admitted that without her looking out for him he would probably be dead. He must have been feeling guilty, because he sent a dozen red roses to the hotel where she was staying in Paris. She wrote back to thank him—a long, newsy letter about the great time she was having and wishing he were there to share it with her. She ended the letter with a question, “How are you, Jackson?” but he didn’t answer.  The next news she got was a phone call telling her that he had been killed in a car crash on August 11th. Edith had also died, and Ruth was injured.

The next news she got was a phone call telling her that he had been killed in a car crash on August 11th. Edith had also died, and Ruth was injured.

Lee was devastated, and flew back from Europe immediately. But she pulled herself together and arranged Jackson’s funeral and burial in Green River Cemetery. His two dogs, Gyp and Ahab, howled as the coffin was lowered into the ground. Jackson’s 80 year old mother, Stella, was there, and she was as stoical as Lee.

Meanwhile Ruth is in Southampton Hospital, and she’s suing Lee for damages. The suit was settled by the insurance company, so her hospital bill was paid, but that’s all. She quickly moved on to a four-year affair with Bill de Kooning. When he made it clear that he wasn’t going to divorce his estranged wife, Elaine, and marry Ruth, she took up with Franz Kline. After he died of heart failure at the age of only 52, Ruth took over his loft and lived there until she died in 2011 at age 80. She was briefly married to the Spanish painter Carlos Sansegundo, and in 1974 she wrote a starry-eyed memoir of her five-month relationship with Jackson, titled “Love Affair.”

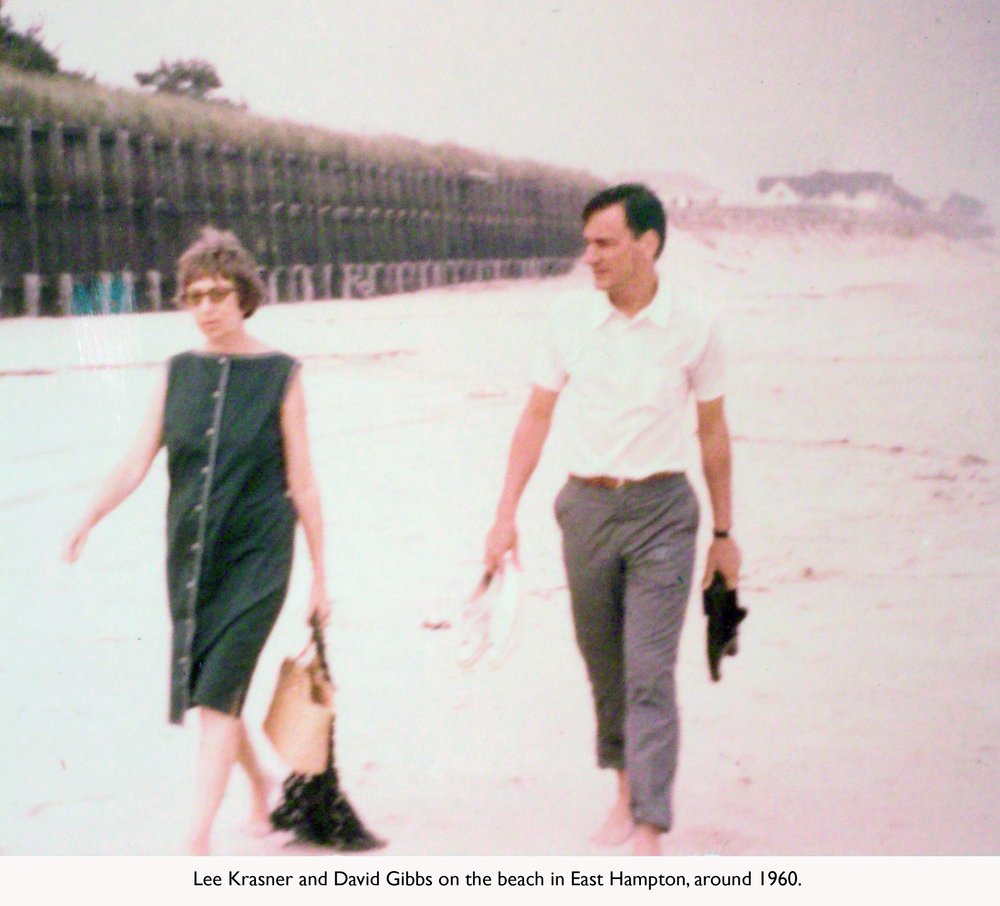

Speaking of love affairs, Lee wasn’t lonely for too long after Jackson’s death. In 1959 she was wooed by David Gibbs, a British businessman turned art dealer with ties to London’s Marlborough Gallery.  She was fifty when they met, he was thirty-three, and his flattering attention and smooth English accent won her over. But David had more on his mind than romance. He wanted to handle the Pollock estate, and he took advantage of Lee’s position as Jackson’s only heir. He wrote her loving letters, and took her on a whirlwind trip around Europe, traveling as a couple while drumming up clients for Pollock’s work. He acted as Lee’s go-between with Marlborough, which showed Pollock’s work in London in 1961 and became the estate’s dealer when the gallery’s New York branch opened in 1964. According to their friends, Lee and David almost tied the knot, but he backed out at the last minute. After that bitter disappointment, Lee gave up on romance, and found her emotional fulfillment in her artwork.

She was fifty when they met, he was thirty-three, and his flattering attention and smooth English accent won her over. But David had more on his mind than romance. He wanted to handle the Pollock estate, and he took advantage of Lee’s position as Jackson’s only heir. He wrote her loving letters, and took her on a whirlwind trip around Europe, traveling as a couple while drumming up clients for Pollock’s work. He acted as Lee’s go-between with Marlborough, which showed Pollock’s work in London in 1961 and became the estate’s dealer when the gallery’s New York branch opened in 1964. According to their friends, Lee and David almost tied the knot, but he backed out at the last minute. After that bitter disappointment, Lee gave up on romance, and found her emotional fulfillment in her artwork.

We could stand here gossiping all day, but I don’t want to keep you. You’ll find lots more details in the books I mentioned, and in Jackson and Lee’s biographies. We sell them in the museum store.