4. Barn studio

As we walk over to the barn, take a moment to consider the importance of the natural surroundings, which inspired both artists. Neither of them painted the landscape literally, but both alluded to things like water, plant life, the moon, and the seasons, in their abstract imagery.

As you enter the barn anteroom through the tall white door, you’ll see baskets containing foam slippers in various sizes. Before you go into the main studio area, you must take off your shoes and put on the slippers to protect the paint surface on the studio floor. Please pick up a pair you think will fit you, take them to one of the benches, sit down and remove your shoes. Don’t put the slippers over your shoes, or go into the studio in bare feet or stocking feet. If you’d rather not use the slippers, you may look into the studio from the steps, but please don’t block people going in and out of the room.

Small children should be carried, or held firmly by the hand. Food and drink must be left in the anteroom. The attendant will be glad to mind your backpack and other bulky belongings. Walkers, strollers and wheelchairs are not allowed on the studio floor. For those who can’t enter, or choose not to, a video tour is available on demand inside the house, which is accessible by a ramp to the front porch from the parking space reserved for the disabled.

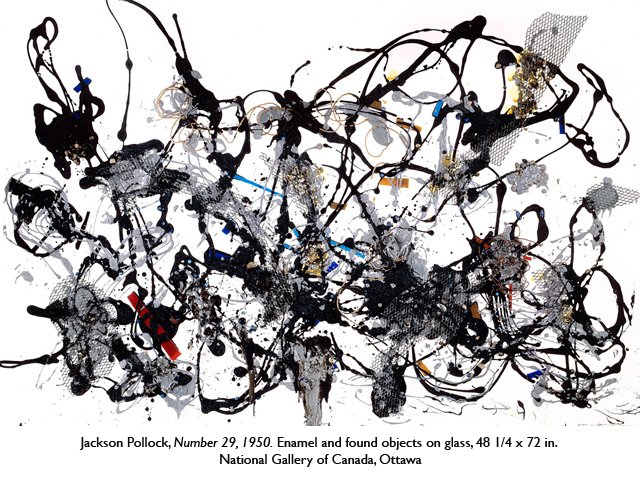

The anteroom is where finished paintings were stored in the wooden racks, and art supplies were kept. There are no paintings here now, but on the shelves and counter you’ll see some powdered pigments in jars, tubes of paint, brushes and tools that belonged to both artists. Lee used some of the strips of colored glass for mosaic tables she made in 1947 and 1948, and two years later, Jackson added some to a painting he did on plate glass, which also contains string, pebbles, wire mesh and other objects.

JACKSON POLLOCK’S VOICE:

In this particular piece, I’ve used sheets of colored glass, plasterer’s lath, beach stones, and odds and ends of that sort. The possibilities, it seems to me, are endless in what one can do with glass. It seems to me a medium that’s very much related to contemporary painting.Yes, that’s a real human skull on the counter. It was a prop from Jackson’s drawing class at the Art Students League, and he took it with him when he left school. To the right of the door are several unopened cans of the liquid house paint Jackson used to make his poured paintings. He used other materials as well, but this type of flowing paint allowed him to get the effects he wanted, and it’s what made him famous.

Across the room, Lee’s paint-spattered boots are displayed on a stool next to the cart that holds her paints and brushes. Nearby is a wheeled dolly Jackson made from a piece of old plywood, and the top of his work table, covered with paint splashes and a scrap of newspaper dated June 27, 1945. That was just before they moved here, so he must have wrapped some of his tools in the paper when he brought them out from the city.

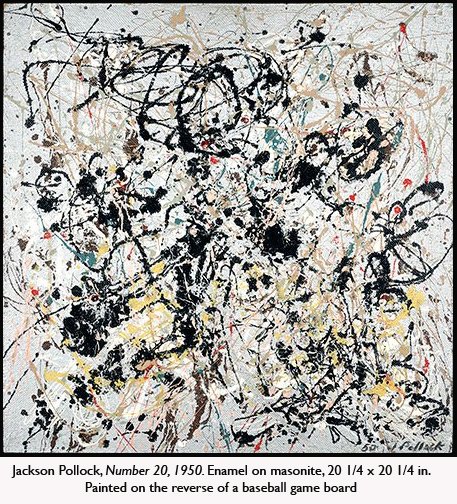

On the wall is a piece of Masonite printed like a baseball diamond. That may seem like an odd thing to have in an art studio, but it helps explain why Jackson’s painting floor is so well preserved. The Autograph Baseball Game, manufactured by the Raff Company in 1948, was actually printed by one of Jackson’s brothers, Sandy, who ran a screen printing business. After the job was done, there were a lot of boards left over, so Sandy gave them to Jackson to paint on. The rough side has a texture very much like canvas, and in 1950 he did a whole series of paintings on the leftover boards.  But he had so many of them that when he decided to renovate the studio in 1953, he used some to cover the floor. You’ll see a few unpainted ones under the storage racks. Inside the studio proper, they were laid down over the floorboards and painted white. The drafty barn walls were insulated and covered with wallboard, also painted white. That’s when the fluorescent lights were installed, so Jackson could work at night if he wanted to. And he put in a kerosene stove for heat, so he could work out here in cold weather. Lee later had the stove removed.

But he had so many of them that when he decided to renovate the studio in 1953, he used some to cover the floor. You’ll see a few unpainted ones under the storage racks. Inside the studio proper, they were laid down over the floorboards and painted white. The drafty barn walls were insulated and covered with wallboard, also painted white. That’s when the fluorescent lights were installed, so Jackson could work at night if he wanted to. And he put in a kerosene stove for heat, so he could work out here in cold weather. Lee later had the stove removed.

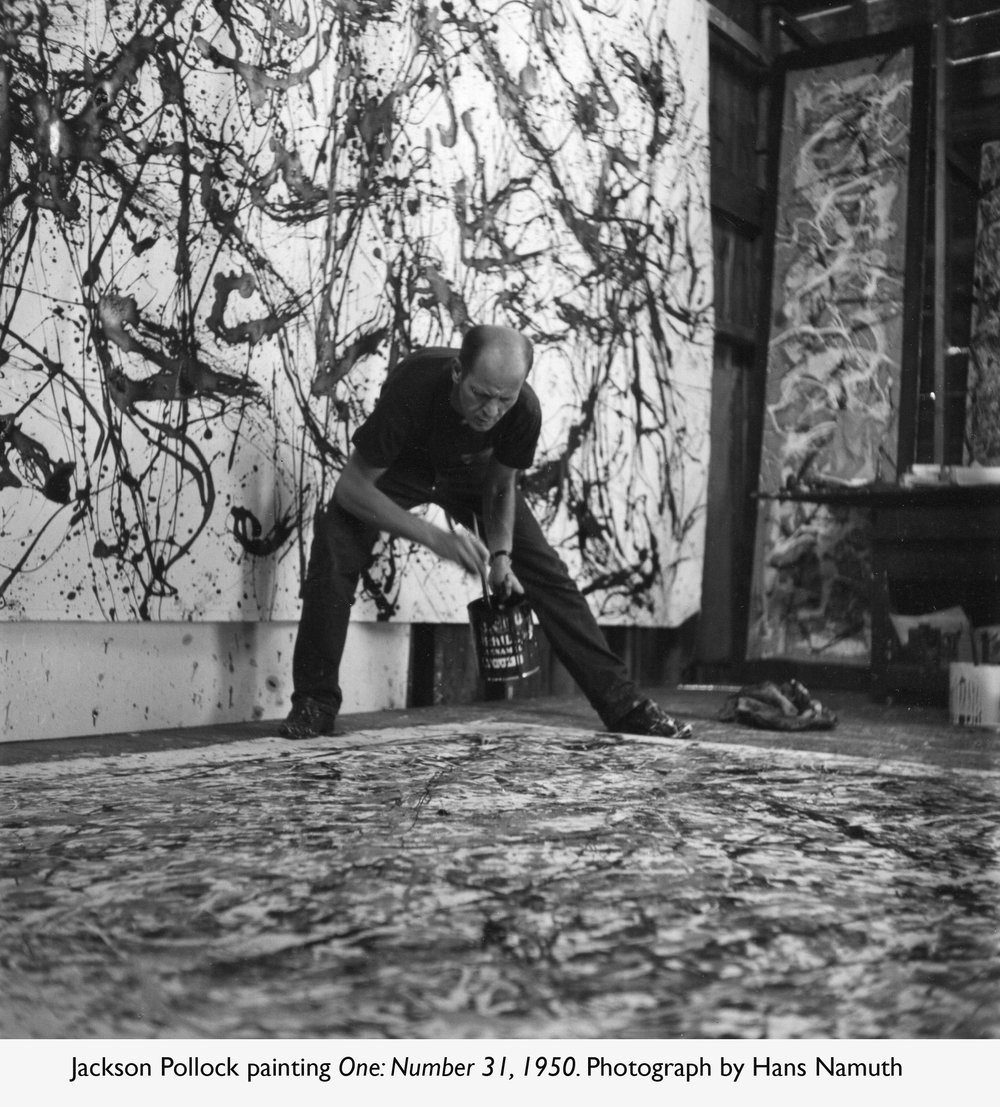

By this time Jackson’s paintings were selling well, and he had enough money to afford these improvements. But he had also begun drinking again after two years of sobriety. While he was on the wagon, from 1948 through 1950, Jackson’s productivity increased dramatically and he created many of his most beautiful paintings, using liquid paints that he poured, flung, drizzled and spattered on canvases laid on the studio floor.  Contrary to what Ed Harris shows in his “Pollock” movie, Jackson did not discover paint-pouring in this studio in 1947. He’d been using it since 1936, when he took part in an experimental workshop in New York, run by the Mexican muralist David Alfaro Siqueiros. Workshop members used liquid paint and spray guns, which were unorthodox in a fine-art context. Siqueiros encouraged them to try new materials and techniques, to be spontaneous, to do whatever gave them the results they wanted.

Contrary to what Ed Harris shows in his “Pollock” movie, Jackson did not discover paint-pouring in this studio in 1947. He’d been using it since 1936, when he took part in an experimental workshop in New York, run by the Mexican muralist David Alfaro Siqueiros. Workshop members used liquid paint and spray guns, which were unorthodox in a fine-art context. Siqueiros encouraged them to try new materials and techniques, to be spontaneous, to do whatever gave them the results they wanted.

What Jackson wanted was to make images that expressed his feelings. He described his work as “energy and motion made visible” and “memories arrested in space.” He painted directly, without preliminary sketches. When an interviewer asked him why he worked that way, he said:

JACKSON POLLOCK’S VOICE:

Well, method is, it seems to me a natural growth out of a need, and from a need the modern artist has found new ways of expressing the world about him. I happen to find ways that are different from the usual techniques of painting, which seems a little strange at the moment, but I don’t think there’s anything very different about it. I paint on the floor, which isn’t unusual. The Orientals did that.His gestures often carried beyond the canvas edges onto the surrounding floor, leaving evidence of the most fruitful and significant years of his short career. Sadly, he wasn’t able to sustain that level of energy and inventiveness, nor could he win his battle with alcohol. As his drinking increased, he painted less and less, until he stopped altogether in 1955. He died the following year in a drunken car crash, at the age of 44.

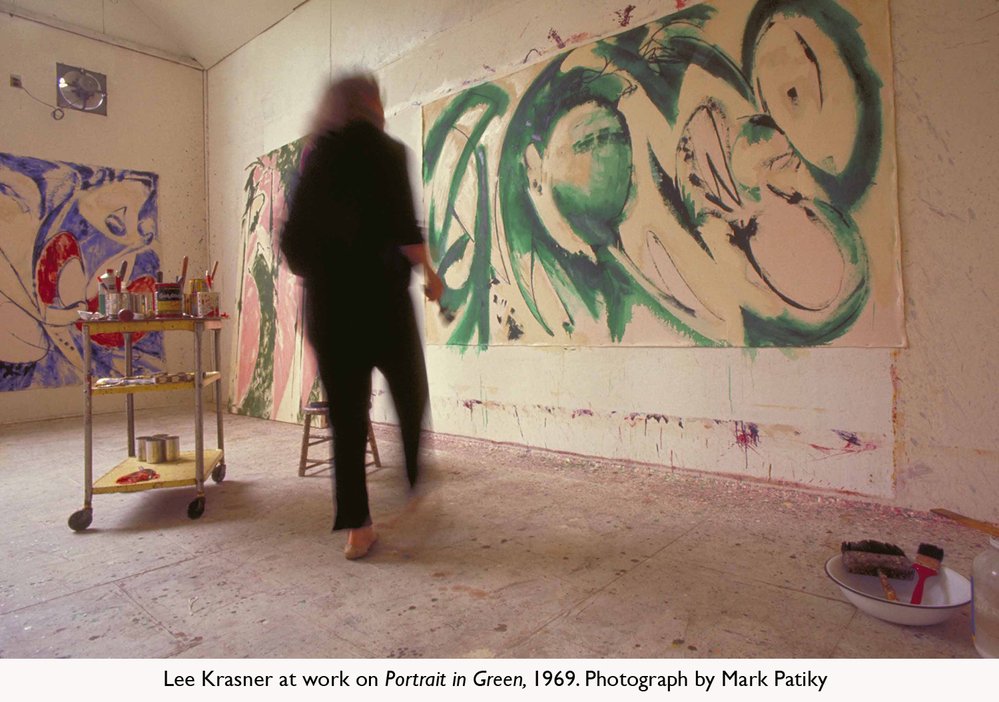

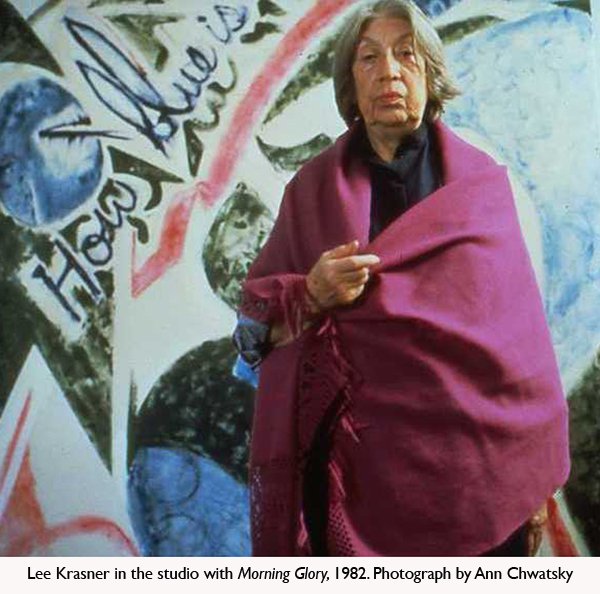

On the studio walls, there’s an exhibition of photographs and text panels that outlines Jackson’s career. A case under the north window contains open paint cans and implements that were left here at the time of his death. The paint strokes on the walls are from Lee's tenure. She worked here from 1957, when she moved her studio from the north bedroom in the house, to 1982, when she finished "Morning Glory," the last painting we know she did in this space.  Her career is also discussed in the exhibition. Like Jackson, she worked spontaneously, with no preliminary plans.

Her career is also discussed in the exhibition. Like Jackson, she worked spontaneously, with no preliminary plans.

LEE KRASNER’S VOICE:

I would start and make some brushstrokes across the entire canvas. And then pretty soon some image will suggest itself to me, and I start out from that, and I keep moving with it.